By Thom Weir, Senior Precision Agronomist

Now is the time to reflect on the season that just wrapped up and try and take some lessons from what we did and what happened. Here are a few observations that I made.

Planting

Planting wheat early, followed by three weeks of cold weather, will successfully germinate and produce a good early crop. That is what both research and crop insurance data would suggest but this year was a little different from a typical year. In mid-April, the Canadian Prairies had some nice weather and by the 20th, some fields could be planted in many areas. While this is common for southern Alberta and SW Saskatchewan, we are talking about areas into the black soil zones of central and east-central Saskatchewan and north-west Manitoba. Then, we had abnormally cool weather well into May. This cool weather resulted in wheat emergence taking three weeks. Pulse crops showed a better response to the cold soils than wheat. But the wheat did emerge and produced some very good crops – albeit a little shorter than usual. These crops did still have a jump on weeds and were ready to harvest before normal-date seeded crops. The comments I heard were that yield, and quality were very good.

The takeaway: Believe the data, and in most years, it is never too early to seed wheat. Two recommendations: 1) use a seed treatment and 2) don’t skimp on the phosphate!

Cutworms on fallow land

Cutworms seem to like soybean stubble and the previous year’s fallow land. Over the past two years, I have been called out on or contacted by growers who have had cutworm issues. Approximately one-half of these calls were related to crops grown on soybean stubble. My guess is the cutworm moths see the green soybean fields in August when they are looking for a place to lay their eggs and think that that is promising real estate. The other cropping situation where I have seen a lot of issues is on fallow land. For whatever reason, if you had land that didn’t get seeded or if the crop was torn up, and there was cultivated bare soil, or you have fields that are in soybeans this year, my feeling is that these fields are where you should consider using seed treatments that have control of cutworms on their label.

Seedbeds

Vertical tillage or similar tillage equipment designed with seedbed in mind and used by many producers for the past few years when excess moisture was an issue – to dry out the seedbed perform as advertised. However, in a spring where many areas didn’t receive rainfall until the middle of June, they did too good of a job. I saw many fields that had very little canola germinate until June 20th and caused issues with harvest this fall. My recommendation is to find alternatives for seedbed preparation unless you have better than average moisture. By using one of these tools and tilling to 12 cm (4”) depth, you will probably lose from 1.5 to 2 cm (.5 – .75 inches) of moisture from that depth. If, like this year where we don’t get a spring rain, crops will suffer.

The crop varieties we are growing and the production practices we are using continue to amaze me with their ability to respond to limited rainfall and less than ideal climatic conditions to produce above-average crops. Even when half or more of a canola crop didn’t germinate until June 20th, it still produced excellent yields when the basics (N, P, K and S) were provided. Investing an 20 extra lbs of N is still probably the best investment you can make in a crop once you have satisfied the P, K and S.

Protein

Protein questions always come up around the first week of July. The most straightforward answer as to how to increase your protein on wheat is to seed it onto a legume stubble. Don’t worry about your “nitrogen credits.” Use your regular nitrogen program, and you will grow an excellent, high protein crop. Get more legumes into your rotation.

Wild Oats

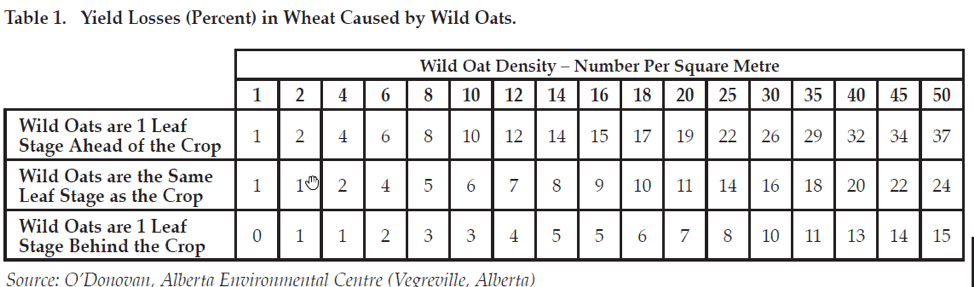

A lot of fields have, in response to several years of excellent control, the wild oat population that is very low. Several cereal fields did not get a wild oat treatment because, at the standard application timing, they had very few plants, well below economic thresholds. To refresh your memory, yield losses in wheat vary by wild oat at density and by emergence date as compared to the crop. The following table was taken from the Manitoba/Saskatchewan Crop Protection Guide.

Estimating a 60-bushel crop, $6.00-bushel wheat and a $18.00 cost of herbicide and application, one would need approximately a 5% loss to break even and a 10% cost to get the 2:1 return often recommended to decide to spray. Across every acre then, a grower would need an infestation of 5 wild oats per square meter (m2) if the wild oats emerged one leaf ahead of the crop and 15 per m2 if they emerged one leaf after the crop emerged. Double these infestations for a 2:1 return. Most of the crops I saw had a few wild oats in the headlands or in the draws, but infestations were maybe 2-3 / m2 and they emerged 2-3 leaves behind the crop. Very few met the economic criteria to spray.

While there will be some wild oat seeds going back into the seedbank, next year’s herbicides will pick them up. Another bonus is one year was saved in the battle with wild oat resistance. Every year that herbicide is not applied is another year where selection pressure was not applied to your wild oat population.

Cleaning out sprayers after herbicide application

Speaking of herbicides, caution should be taken when cleaning out sprayers following Gr. 2 herbicide applications. There is more and more of the “generic” group 2 products Trifensulfuron/Tribenuron which use older formulation techniques. These products, as well as newer products such as PrePass Flex, have the issue of hanging around in sprayers and plumbing and only coming out if thoroughly cleaned (including all filters and strainers) or when Liberty is used. This results in significant damage to the canola. This can occur after several sprayer tank loads of herbicide. I looked at a few fields showing damage.

Weather and Predictive Modeling Tools

I have a couple of observations on the weather and predictive models. We had an average year of precipitation in much of the Canadian prairies. However, it was very dry for the first six weeks and very wet for the last six weeks. It was a bit cooler, especially during May and June, and crop delays carried on throughout the year. Crop Staging predictors do work. I have been using one and it has been scary accurate for most of the year. The disease and insect models also worked. When they said low risk for Fusarium or Sclerotinia infections, low disease pressure was observed. It was OBI-WAN KENOBI who said, “Use the Forecast, Luke” – or something to that effect. The forecast models work and as we get more and better local weather information, they become more accurate on your farm.

And finally, I am convinced Climate Change is real. One of the consequences of Climate Change is more violent shorter term and longer-term swings in weather that results in more erratic weather. We saw it this year – from very dry to very wet, cooler than normal etc. Don’t be surprised when we have springs – or falls – or summers like we had this year. Because of these swings, growing crops like soybeans or corn may result in frost damage (the average first day of fall frost is still the second week of September in much of western Canadian prairies) and the prospects of having to wear your Halloween costume when combining.

I hope this gives you some insight as you plan for the 2020 season. Join one of our upcoming webinars to stay up-to-date on our suite of digital ag tools.